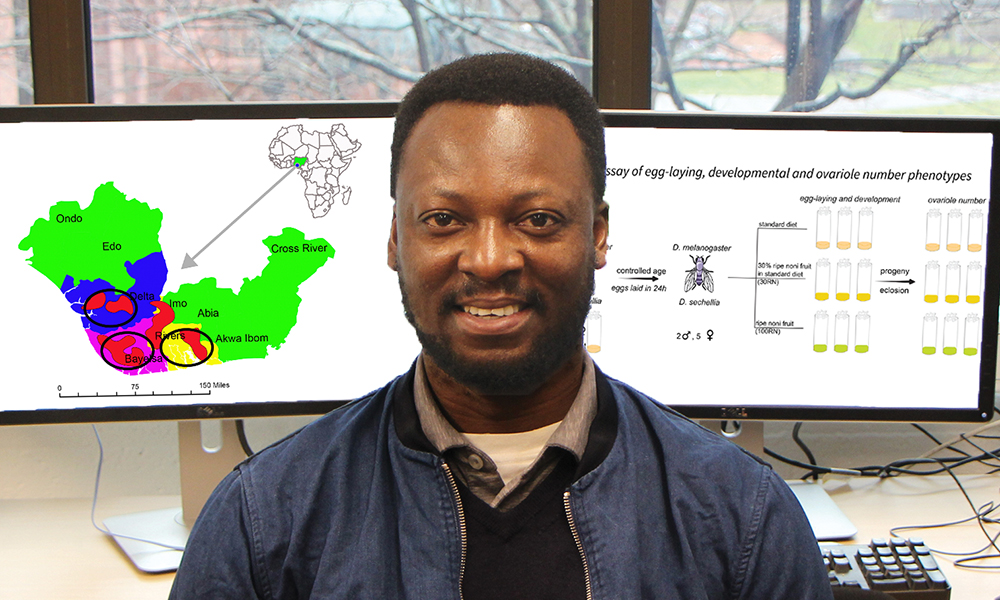

Postdoc Olakunle Jaiyesimi of the Extavour Lab is using metabolomics, or the study of an organism’s global metabolic products, to address questions about the effects of the environment on reproductive and developmental traits. In the Extavour Lab, he conducts experiments on two closely-related species of Drosophila flies that have very different responses to toxic noni fruit. He also collaborates with labs in Nigeria to assess the health impact of oil pollution in the Niger Delta, a project for which Jaiyesimi and his advisor Cassandra Extavour received an award from the Motsepe Presidential Accelerator Fund for Africa.

In both projects, Jaiyesimi employs a metabolomics approach, where he assembles a list of all the small molecules present in samples, annotates these compounds, and determines the biochemical pathways involved. “Metabolomics highlights a list of small molecules that correlate with phenotypes of interest,” Jaiyesimi says. “Because many phenotypes are influenced by more than one gene or pathway, you can use the list to make biologically meaningful interpretations regarding the small molecules, pathways, or genes involved in your specific question. Metabolomics actually tells you what this person has become metabolically versus what the person is expected to be. So, metabolomics has the potential to unravel the often observed intra-specific or intra-population phenotypic variations.”

“Olakunle has more passion than almost anyone I’ve ever had the pleasure to work with in science—passion for science, passion for discovery, and passion for life,” says Jaiyesimi’s advisor Cassandra Extavour. “There is never a simple answer to anything as far as Olakunle is concerned, and that fact, the inescapable complexity and interconnectedness of the biological world, is the beauty of science that he is so in love with. He is highly creative and imaginative, and is never afraid to throw out a dozen new potential hypotheses for a new observation. There is no level of biological organization that he does not find fascinating rather than daunting, no negative result that he does not see as opening new doors of challenging enquiry rather than as discouraging. He has brought new life to the lab not just in the form of metabolomics analysis, but also in his inexhaustible, tireless enthusiasm, engagement, and sincere fascination with the work and lives of everyone on the team.”

Jaiyesimi originally hails from Ijebu in Nigeria, where his father worked as a forest officer and his mother worked as a teacher. From an early age, Jaiyesimi had a curious mind, which led him to study Pharmacy as an undergraduate at Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife. The first few years after the founding of the University went smoothly, until years of military dictatorship caused disruptions, such as power outages and faculty and student strikes. For his final year and Master’s degree in Pharmacognosy, Jaiyesimi studied the potential of ethnomedicinal antidiabetic plants to prevent the progression of prediabetes to diabetes.

Although Obafemi Awolowo University is one of the most celebrated universities in Africa, scientific instruments were scarce, so he applied for Ph.D. programs overseas. The search led him to Leonardo Gobbo-Neto’s lab at the University of Sao Paulo in Ribeirão Preto. Jaiyesimi arrived in Brazil not speaking a word of Portuguese, but he adapted. “The way I think about it is: many of my peers, even younger folks, are on the war front,” he says. “They are battling wars, they are battling for their lives…. And here I am sitting in a class, learning in Portuguese…It could have been worse.”

With access to liquid-chromatography-mass spectrometers and other instruments, Jaiyesimi learned more about the science of small molecules. He identified bioactive compounds in 68 medicinal plants from Nigeria and Brazil with potential to reduce, prevent, or delay hyperglycemia. “My research journey was just beginning,” he says. “Because, although metabolomics had offered me a glimpse into organismal metabolism, some questions remained, including the role played by host microbiomes and their interaction with environmentally-sourced small molecules.”

He then secured a postdoc with the Garg Lab at Georgia Tech. There, he conducted metabolomic analyses of host-microbe interactions in contexts including Burkholderia bacteria, which infects cystic fibrosis patients’ lungs, and on corals affected by stony coral tissue disease.

Jaiyesimi’s search for a follow-up postdoc where he could investigate an organism’s metabolome holistically led him to the Extavour Lab at Harvard. For his main project, he studies the mechanisms underpinning the impact of a niche environment on reproduction and development, using two species of Drosophila as a case study. Drosophila sechellia lives on ripe noni fruit in the wild, but other species, such as Drosophila melanogaster, are incapable of surviving or reproducing on noni fruit, and they avoid it.

Jaiyesimi fed both species mixtures containing different ratios of noni and standard laboratory fly food. He found that at moderate concentrations, the noni fruit led to increased egg-laying in both species but was toxic to D. melanogaster larvae. However, D. sechellia tolerates the ripe noni fruit. Jaiyesimi is now exploring the metabolome of the fly samples to generate testable hypotheses that could explain the differing responses.

In the project funded by the Motsepe Presidential Accelerator Fund for Africa, members of the Extavour Lab are working with the Abolaji Lab at the University of Ibadan and the Drosophila Research and Training Centre, Ibadan, to collect soil, water, and local Drosophila fly samples from communities in the Niger Delta. Jaiyesimi and his colleagues aim to use flies as biosensors and experimental test subjects for understanding how oil-pollution may be impacting health. They’ll analyze gene expression and metabolic profiles to identify which pathways are most affected.

Jaiyesimi expresses gratitude for his experience at Harvard. “I’m grateful to Cassandra for her mentorship, to all my supervisors before now, and to the Harvard community for all the opportunities that I have been given,” he says. “I will always be grateful to my family–my parents, my wife, my children.”

The advent of AI image generators and chatbots has generated a new outlet for his creativity. “The problem is since I started my Ph.D., I’ve not been able to exercise my creative mind as I would want,” he says. “Every time I use my creative mind, I am happier.” Today, Jaiyesimi hosts a Facebook page and other social media, where he posts AI-generated artwork that pairs with his sayings. Many of these posts go viral as soon as they are minted. One of the adages Jaiyesimi lives by is “Be intense in the moment. The fate of entire futures resides in the current second.”

Jaiyesimi also serves on the Community Task Force for Equity Diversity Inclusion and Belonging (EDIB). He was on the Research Retreat Committee last year and is currently on the Safety and Support Working Group.

Going forward, Jaiyesimi is focusing on his current research and seeing where it leads. He plans to stay in research but also has an idea for a startup that offers metabolomics solutions to underserved communities.

Olakunle Jaiyesimi and his art:

“This image speaks to my research interest on the impact of the environment on phenotype. It illustrates the impact of anthropogenic activities on the health of corals, complicated by climate change.

This visual marvel was created using a publicly available custom GPT-4 based agent I built using OpenAI’s ChatGPT 4, named “AP HyperImage”. Post-creation, the image journeyed to Canva, where text and speech bubbles were added. Time it took from start to finish: < 10 minutes.”