Olfaction is a critical sense for many animals, guiding their foraging behavior, mate choice and predator avoidance. Mice use ~1000 odorant receptor types in the main olfactory system to probe chemical space. In vertebrates, odors are sensed by olfactory sensory neurons (OSN) in the nose, each of which expresses one out of ~1000 odorant receptors. All sensory axons expressing a particular receptor then converge on ~2 glomeruli in each hemisphere of the olfactory bulb. Since each glomerulus receives input from a single type of odorant receptor, each point on the surface of the olfactory bulb has a specific chemical response spectrum. Within each glomerulus, sensory axons make synapses on several postsynaptic targets including the primary dendrites of one to two dozen mitral/tufted (M/T) cells, which are the output cells of the bulb. A given M/T cell receives excitatory input from a single ‘parent’ glomerulus through its primary dendrite, and makes lateral connections with several types of inhibitory interneurons. The olfactory bulb also receives massive feedback projections from higher brain areas, which allow “top-down” control of sensory coding.

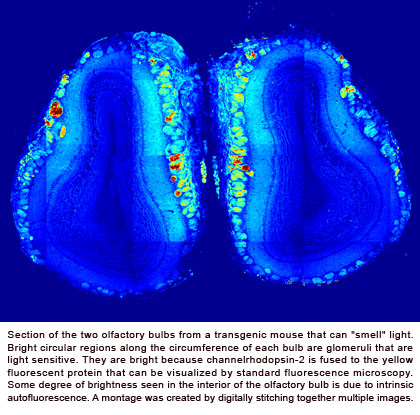

The computations performed by a neural system such as the olfactory bulb are constrained by its architecture. Progress in understanding the circuitry and information processing in the olfactory system has been hampered, in part, due to imperfect control of odor stimuli and the difficulty in stimulating arbitrary combinations of glomeruli at will. A further complicating factor is the poorly understood topography of sensory inputs to the olfactory bulb – neighboring glomeruli can often be functionally dissimilar. We reasoned that direct glomerular activation (bypassing smells) might overcome these limitations and enable more detailed studies of functional circuitry in the olfactory bulb and its projection areas. Therefore, we generated transgenic mouse lines that express a light-activated ion channel channelrhodopsin (ChR2) specifically in olfactory sensory neurons, rendering the input layer of the olfactory bulb (glomeruli) optically excitable. Essentially, these mice will get the sensation of smell when blue light is shone on their noses. We can now systematically activate glomeruli in arbitrary spatial and temporal patterns, allowing us to manipulate the system with unprecedented degree of control.

We used these mice to make an exciting discovery about how odors are coded in the olfactory bulb. As mentioned above, a group of M/T cells (sister cells) receive primary input from a single glomerulus and are thought to respond similarly to odors. A rigorous test of this view of response similarity has not been undertaken due to difficulty in properly identifying sister cells. In this study, we could easily identify sister cells because they responded to light shone on the same spatial location on the surface of the olfactory bulb. This identification was made routine by an instrument we developed that could project arbitrary patterns of light on the olfactory bulb. After identifying sister cells in this way, we examined their responses to dozens of odorants. At first blush, the responses of sister cells seemed to be highly similar. However, the exact timing of spikes emitted by sister cells were quite different and contained additional information. Therefore, olfactory bulb circuits process the incoming information and send out smell information coded both in the average activity of output cells as well as the precise timing of their spikes. The challenge now is to determine if and how these different channels of information are used by the multiple target brain regions.

Stepping back to take a broader view, the tools developed in this study –transgenic mice that smell light and the patterned light stimulation technology – will help advance our understanding of odor coding. In addition, since olfaction is often used as a sensory gateway to study higher brain function such as decision making, our tools are likely to have broader use in neuroscience.

This work was done in collaboration with Florin Albeanu’s lab at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York and Upinder Bhalla at National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India.

Read more in Nature Neuroscience (Advance Online Publication)

Read more in The Harvard Crimson

Hear more on NPR (Morning Edition)