Iron is a key micronutrient that organisms use in many biological processes. Indeed, aerobic respiration requires iron to transport oxygen in our blood, to catalyze redox reactions of metabolites in our cells, and to provide the pathway for electron transport in our mitochondria to generate ATP, the cellular energy currency. Because of iron’s many essential roles, iron deficiency famously causes anemia, a disorder that afflicts almost a third of the world’s population. Organisms throughout the tree of life use the Nramp (Natural resistance associated macrophage protein) family of transition metal transporters, which move iron and other metal cations across biological lipid membranes, to acquire and traffic iron. In humans and other mammals, Nramp1 works to starve pathogens of essential metals as part of the innate immune response to infection (thus explaining the “Nramp” name), while Nramp2 enables the uptake of dietary iron in the intestines. In work just published in Structure (PDF) we use a bacterial Nramp as a model system to understand at the atomic level how Nramps work and how mutations in Nramp2 cause anemia.

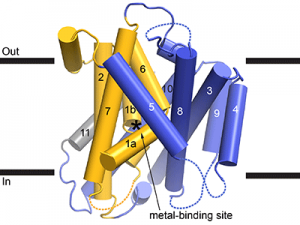

As a framework to understand how these important metal transporters work, we crystallized and determined the 3D molecular structure of this bacterial Nramp. The structure resembles that of distantly-related transport proteins, providing a few clues as to how Nramps transports metals. While crystallography provided a static snapshot, we know transport proteins like Nramp must rearrange into multiple conformations to move cargo across the membrane. Metal is first taken up while Nramp is in an “outward-facing” conformation with a water-filled pathway from outside the cell to the metal-binding site in the heart of the protein (see Figure). Metal is then released inside the cell by a second, “inward-facing”, conformation that instead forms a new water-filled pathway from the metal-binding site to the cytoplasm. The structure we obtained is inward-facing and contains no metal, and thus represents Nramp in a post-cargo-release conformation. To complement this structure, we used biochemical assays to locate the aqueous pathway the metal ion takes in the alternate outward-facing conformation.

Nramp transporters alternate between an outward-facing conformation (left) and an inward-facing conformation (right, captured in our new crystal structure) to transport iron ions across biological membranes (grey). Anemia-causing mutations act as wedges (red triangles) that prevent the conformational changes required for iron transport. In the current model, the yellow “bundle” rotates within the blue “scaffold” as the transporter changes conformation.

We also sought to explain how two naturally-occurring point mutations cause anemia on the organismic scale. Introducing either of these amino acid changes (both replacing a small and flexible glycine with bulky and charged arginine) impedes iron transport. Because the mutated amino acids are located far from the metal-binding site, we used biochemical assays to test the hypothesis that they disrupt the conformational change process. Indeed, one mutation (G153R in our bacterial transporter) both interferes with the closing of the outward-facing water-filled pathway and alters the metal selectivity to disfavor iron. The second mutation (G45R) acts as a wedge that blocks structural rearrangements and locks the Nramp transporter in an inward-facing conformation. This thus prevents metal ions from ever reaching the binding site from outside the cell.

In conclusion, our atomic-resolution structure of an Nramp iron transporter enabled us to explain the molecular basis for two anemia-causing genetic mutations and provides a scaffold for future investigations into the molecular mechanisms of this important iron transport machinery.

Cartoon representation of the Deinococcus radiodurans Nramp crystal structure, viewed from within the plane of the membrane. The transmembrane (TM) helices labeled; the bundle (TMs 1, 2, 6, and 7) is gold, scaffold (TMs 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, and 10) blue, and TM11 gray. Dashed loops are disordered in the structure. The position of the metal-binding site is indicated by an asterisk.

Authors: Aaron T Bozzi and Rachelle Gaudet